I myself grew up in a small town, Seward, Nebraska, and attended its Lutheran high school, which prohibited dances. I attended as a freshman and sophomore during 1966-1968. In 1968, following years of discussions between the students and the faculty, the prohibition was removed and the students were allowed to have their first dance. Thus, I myself experienced the rather unusual situation that the Footloose story depicts.

When the first Footloose movie was released in 1984, I read reviews and knew the essential story, but I decided not to see it despite my own similar experience. My reluctance was caused by my assumption that the movie would treat the dance-ban conflict between the Church and the students in an offensive, anti-religious manner.

However, about 20 years later, in about 2005, I caught the movie’s beginning while I was channel-surfing my television, and I watched the entire movie. I found that I liked the movie and also that its portrayal of Christians was rather understanding and sympathetic.

The movie resonated with my own memories of how the dance controversy had been resolved in my own Christian high school. For me this resolution is a happy memory, because this decision to end the dance ban resulted from polite, respectful, persistent talks between the adult faculty members and the young students. Both in the movie and in my high-school experience, Bible verses were used in the debates as evidence in favor of dancing.

I liked the movie’s portrayal of the Christian family. The pastor’s daughter is the movie’s female lead, and her parents are important supporting characters. Several of the scenes take place in their church and include parts of three sermons. The pastor, his wife and their daughter behave and talk in a manner that is realistic for such a family. They are religious and intelligent.

The 1984 movie depicted Christians as engaged in a couple of controversial activities – preaching about Hell and banning books from school – that probably most viewers would consider to be distasteful or even contemptible. The 2011 movie does not, however, depict those particular activities. Most people watching the 2011 movie would find that the Christians are portrayed quite positively.

In both movies, the pastor’s daughter rebels against her Christian upbringing, but then reconciles with her family at the end. This rebellion and reconciliation are more vivid in the 2011 movie.

The 2011 movie adds a second Christian family to the story. The boy who comes to the small town moves in with his uncle’s family, which displays its Christianity in an admirable manner. The uncle’s family prays before meals, attends church every Sunday, and donates money to people in need. This family is generous, kind, happy and well adjusted.

In the 1984 movie, the pastor and his wife (Shaw and Vi Moore) were played by the actors John Lithgow and Dianne Wiest.

I felt that these two characters were likeable and even admirable. They were not the villains I had expected. They treated their daughter and other people in a nice manner, they spoke intelligently about the dance issue in their town, and eventually they decided publicly to change their minds and support the young people’s desire to dance.

Thus the movie resonated with my own memories of how a similar issue had been resolved in my own youth. There had been polite and respectful conversations that led eventually to the removal of a restriction and to a change of attitudes. When I thought back to these memories of my own youth, the resolution of the dance prohibition was a positive and happy memory about how adults and youths had worked out a difficult but successful reform in our local Christian community. I thought that the movie shed a similarly positive light on the resolution of its own similar conflict.

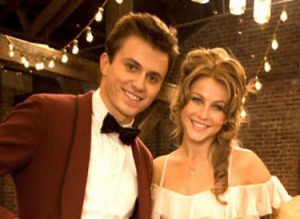

I found that the 2011 movie was even better and that its portrayal of the pastor and his wife -- played by Dennis Quaid and Andie MacDowell – was even more positive.

The Footloose story is based on an article that appeared in People magazine in 1980, about the Oklahoma town of Elmore, population 653, which had banned public dancing ever since the town was founded in 1861. In January 1980, some students petitioned the town council to allow dancing at a school prom.

The People magazine’s article described the opposition to the dance as follows:

"No good has ever come from a dance," thundered the Rev. F.R. Johnson of the United Pentecostal Church in nearby Hennepin—the father of two teenage daughters. "If you have a dance somebody will crash it and they'll be looking for only two things—women and booze. When boys and girls hold each other, they get sexually aroused. You can believe what you want, but one thing leads to another."After the debate, however, the town council voted 3-2 to permit the dance. The article’s description of the subsequent events was charming:

The Rev. Johnson insisted he spoke for many of the churchmen in the area and many of their parishioners. At a town meeting to consider the question in February, a local citizen predicted that after the dance there would be a surge in pregnancies at the school "because when boys and girls breathe in each other's ears, that's the next step."

… the kids decorated the school cafeteria so lavishly that even John Travolta would have felt at home. The theme of the prom was Stairway to Heaven, the Led Zeppelin standard that was also the opening dance. The room was decorated with blue paper sprinkled with silver stars, an aluminum-foil moon and a spiral "staircase to heaven" made of sequined cardboard.

Arriving in their Sunday best at 7 p.m., the kids sat down to chicken-fried steak, mashed potatoes and gravy, fried okra and strawberry shortcake, then changed into jeans for the evening's serious business—showing off the fancy steps many had been rehearsing in front of mirrors for weeks.

Maybe it should have been months. "Shoot," groaned one porky lad, watching with his buddies from the sidelines, "I sure wish they'd play more slow songs. I can't do that fast stuff yet." Another novice caught her breath by an open window. "I got me a side-ache," she confessed, falling into a chair. "I'm not used to this."

Girls found it easier going than the boys. "He don't dance," complained one blonde, nodding with disgust at a lanky youth in denim. "He kicks and steps on you. He'd probably bite, too, if you didn't watch him."

Not all the males had two left feet. Cool and collected Mike Niblett, 17, was first out on the dance floor with his date, Catherine English, 18, and later won the limbo contest. His secret? "A lot of us have gone to dances before," Mike explained, "but we've always had to drive far away to do it."

When the prom was over, all the dire worries had proved groundless. "It went exactly like I thought it would," said Superintendent Kirby. "They're a fine bunch of youngsters." Asked if next year's class would also get their prom, Kirby would say only "We'll see." But the school board will have problems keeping 'em down in Elmore City now that they've heard the beat.

Class president Rex Kennedy said with a grin: "We thought about asking for permission to dance at the next Future Farmers of America meeting, but I guess that's pushing our luck."

This true story was turned into a movie script by Dean Pitchford, who was born in 1951 in Hawaii. As a youth he performed as an actor and singer in the Honolulu Community Theater, the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra and the Honolulu Theatre for Youth. He enrolled in Yale University and majored in drama. In 1971 he performed in off-Broadway performances of the musical Godspell, and in 1972 he played the lead role in Bob Fosse’s Broadway musical Pippin.

After Pitchford read about the situation in Elmore, Oklahoma, he wrote a screenplay and also collaborated with various musicians – Eric Carmen, Michael Gore, Sammy Hagar, Kenny Loggins, Tom Snow and Bill Wolfer – on nine songs that eventually were included in the movie.

The movie cost only $8 million to make, and it grossed about $80 million in the theaters. The soundtrack album rose to #1 on the US Billboard’s album chart (knocking off Michael Jackson’s album Thriller) and remained at the top for ten weeks. The album sold 17 million copies worldwide. The album’s first two songs – “Footloose” and “Let’s Hear It for the Boy” – both reached the #1 position as single songs.

It is apparent that Pitchford was captivated by the People article's element that the most prominent opponent of the prom dance was a Pentecostal pastor with two teenage daughters. This pastor was concerned especially that the dance would attract male strangers to come from distant locations to crash Elmore’s prom and intoxicate and seduce the local girls:

“If you have a dance somebody will crash it and they'll be looking for only two things—women and booze. When boys and girls hold each other, they get sexually aroused. You can believe what you want, but one thing leads to another."This concern suggested to Pitchford his screenplay’s central conflict – a boy would come from a distant place into the small town and would violate the small town’s dance prohibition and thus seduce the daughter of the Christian pastor who tried to uphold the dance prohibition.

The end of the dance prohibition in Elmore, Oklahoma, coincided roughly with the end of the Presidency of Jimmy Carter. The prom took place in about May 1980, and Carter lost his campaign to be re-elected in the election of November 1980.

Carter was a devout Christian who had grown up and remained in the small Southern town of Plains, Georgia. During his long political career, he used his Christian religion as a motivation and tool to promote racial integration and for other political reforms in his town and state. A major factor in his successful campaign for election to President in 1976 was that his Christian morality and stability seemed to be a refreshing improvement over the preceding ten years of what many people considered to be undisciplined and immoral.

Carter turned out to disappointment as President. Unemployment and inflation soared, people had to wait in long lines to buy gasoline, and Carter was not able to free the US citizens who were held hostage in Iran.

Carter seemed to be a moral man who was too proper to succeed as President. He meant well, but he was overwhelmed by troublesome forces and too finicky about making tough decisions that might leave some people as victims.

In that same 1980, Pitchford turned 29 years old and began to write his screenplay about a pastor who had a teenage daughter and who tried to maintain his small town’s traditional prohibition against dancing. I don’t know whether Pitchford had grown up in a Christian environment, but I do suppose that the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter family, at least to some extent, influenced his ideas about how a pastor and his wife might discuss with each other their concerns about how their teenage daughter might be endangered by a sudden, new exposure to sexy dancing.

In order that such reasonable and modern parents might have an understandable basis for their fear of dancing, Pitchford wrote into his story a previous tragedy –“five or six years” earlier, their son and several other high-school seniors had died in a drunken car crash after a school dance. Therefore the town council had banned all future dances, and therefore much of the small town’s population supported this pastor in his stubborn advocacy for a continued ban.

I suppose that Pitchford did most of the writing work on his script during about 1981 and 1982, which was five or six years after 1976 or 1977, which were the years when Carter was elected and became President. If Pitchford did, perhaps subconsciously, use the Carters as his model for the pastor and his wife, then he started his story with an event that had happened “five or six years earlier” – with the beginning of the Carter Administration in the case of the Carters and with the tragic car accident in the case of the pastor and his wife.

I am not saying that the Carter Administration was like a car accident. Rather, I am saying that Pitchford was imagining how a devout but modern Christian couple might discuss between themselves a re-assessment of their situation after a certain time period – a period short enough that they still were very emotional but long enough that they should be objective.

In each case the husband (Jimmy Carter and the pastor) was still emotional and stubborn after five or six years, whereas the wife (Rosalynn Carter and the pastor’s wife) had become objective and flexible. The wife gently persuaded the husband to reconcile himself to his loss and to look forward to new perspectives and rethinking.

In the 2011 movie version, the time since the fatal car accident has been changed from five-six years to only three years. I think the shorter interval improves the story, because Ariel would have been a high-school freshman (not a fifth grader) when her brother died in the accident.

Since the story is about a high-school-senior prom, the pastor’s daughter in the story is a high-school senior – now the same age as her brother who had died after a high-school-senior dance several years earlier. This coincidence confronts her with her own mortality. Just as her brother died suddenly in his senior year, so she too might die in this year.

Along with her brother, several other classmates died in that same car accident. Therefore the pastor’s daughter is not alone in her own senior class in her premonition of her own possible death during this year. On weekend evenings, many of her classmates gather in a shed close to a nearby railroad track. When a train approaches, they stand in the middle of the tracks until the train almost hits them, and then they jump away. They are excited by the danger, and afterwards they lie along the tracks and make out with each other.

Some of the young people also play dangerous games in which they race and almost crash large vehicles – in the 1984 movie they do so with tractors and in the 2011 movie they do so with old school buses. The pastor’s daughter becomes involved sexually with an older boy -- about the same age as her deceased brother -- who plays such games. She is passionate more about the dangerous games. She would prefer not to engage in sexual intercourse with this older boy, but she does so that he will not dump her.

Of course, she conceals all such activities from her parents and she lies to them constantly. She resents them because she feels they still grieve more about her dead older brother than they care about her. She feels that other young people in the town blame her family for the town’s prohibitions against dancing and for the curfews. As soon as she graduates from high school, she wants to leave the town forever.

Then during the middle of the senior year, a new boy – his name is Ren McCormack – comes to live in the town and is introduced to the pastor’s daughter – her name is Ariel Moore – after a church service. In the following days, during and after school, Ariel flirts with Ren in an effort to attract him. She shows him the place at the railroad track, and she stands on the track as a train approaches. She arranges for him to participate in the other dangerous game with the large vehicles. She drops her older boyfriend so that she is available to Ren, but Ren is keeps his distance from her because he is dismayed by her dangerous behavior.

In the 1984 movie, the characters Ren and Ariel were played by the actors Kevin Bacon and Lori Singer.

Ren’s mother grew up in the small town and then moved away to a large city (Chicago in the 1984 movie; Boston in the 2011 movie; the actor Wormald speaks with a delightful, native Massachusetts accent). In that big city, she gave birth to Ren (the story does not say whether the pregnancy began in the small town or in the large city). Then, when Ren was a school boy, the father disappeared, leaving the mother and Ren alone and without support.

In the 1984 movie, the mother returns to the small town with Ren. In the 2011 movie, the mother dies in Boston after suffering for a long time from leukemia, and so the orphan Ren comes to the small town to live with his mother’s brother (Ren’s uncle).

Although Ren is dismayed by the dysfunctional manner in which the small town’s young people have been dealing with the emotional trauma caused by the fatal car accident, he himself is dealing with several emotional traumas of his own. He had grown up without his father, and now he had been taken away from his friends and surroundings during the middle of his senior year and had been thrown as a stranger into a small town’s senior class, where newcomers were hassled. In the big city, he had excelled in gymnastics, a sport that essentially was unknown in the small town. The 2011 movie adds the trauma of his mother’s recent death from leukemia; he was orphaned and had come to the small town to live with his mother’s brother.

Trying to adjust to his new life in the small town, Ren sometimes becomes frustrated or upset, and he deals with his emotions by going to an empty warehouse, where he performs gymnastics and dances. His own recognition that his own self-therapy is more sensible and healthy than the local young people’s dangerous games motivates him to encourage the local young people to dance and to lead a protest against the small town’s restrictions on dancing.

Ren’s efforts lead him into a conflict against the pastor, who is the town’s main advocate for maintaining the restrictions on dancing. The screenwriter Pitchford has mentioned in an interview that his story features a conflict between two protagonists: 1) a boy who has lost his father, and 2) a father who has lost his son. This relationship becomes obvious once it is pointed out, but it is not depicted as an explicit factor in the two characters’ eventual resolution of their conflict. Each character seems to be chronically obsessed with his own loss, and I myself did not perceive that either Ren or the pastor recognized the other as a potential replacement for his own loss. This particular element (fatherless boy vs. sonless father) of their interaction is quite subtle in both movies, and I think it passes below the attention of most viewers.

However, Ren’s loss of his own father does explicitly motivate his own actions. Both movies include an incident in which Ren is asked why the dance issue has become so important to him. What real difference does it make to him whether or not the school can have a dance? Why is he investing so much time, effort and emotion into this controversy, when he probably will leave the town immediately after graduation anyway?

In both movies, Ren’s answer is similar. Since I have a transcript of the 1984 movie, I will quote it:

When Dad first threatened to leave, I thought it was because of me. I thought it was something that I wasn't doing right. And I figured there was something I could do to make it like it was, and then he'd want to stay. But when he left, just like that, I realized that everything I'd done -- hoping that he'd stay -- didn't mean shit. And I felt like: ''What difference does it make?''In other words, life has meaning for a person when he can exert some positive effect on other people. The opportunities to exert such influence are limited, because eventually we disappear – we leave or we die. So, seize your opportunities to exert positive influence while you do still have them.

But now -- now I'm thinking I could really do something. You know, I could really do something for me this time. Otherwise I'm just going to disappear.

In the 1984 movie Ren’s father disappeared by abandoning his family. In the 2011 movie Ren’s mother disappeared too, by dying of leukemia. So, Ren was very aware that we all eventually will disappear from the lives of the people close to us and around us.

Ren realized that he could make a valuable contribution to the small town, by enabling its young people to relieve their stress and anxieties by dancing rather than by acting-out in self-destructive behavior. He found himself in the right place at the right time with the right potential contribution, and that is why his efforts in this controversy had become so important to him.

This is the movie’s main moral lesson: Help other people when you have the opportunities.

During the Carter Administration, there were four successful movies about dancing. The Turning Point (1977) depicted lives of professional ballet dancers, All That Jazz (1979) depicted the lives of professional musical dancers, Saturday Night Fever (1977) depicted the lives of semi-professional dancers who competed in dance contests, and Fame (1980) depicted the lives of students in a special school for future professional dancers.

In the decades before the Carter Administration there was a long series of musicals in which dancing was an artificial device inserted into stories that were not essentially about dancing. For example, gang members in West Side Story would dance and sing during their knife fights. The movie Grease (1978) was a musical in which the story revolved around a high-school dance, so the characters danced for a story-related reason and so also the characters danced with ordinary skill.

Thus, Pitchford began writing Footloose during a period when there was a development of realistic movies (not traditional musicals) about skilled, competitive dancers. These movies featured expert dancing, because the stories were about characters who danced expertly. Footloose was the first realistic movie (Grease had been a musical) about ordinary people who were learning to dance for pure fun and so did not dance expertly.

One character, Ren, did dance with extraordinary skill, because he had been a gymnast at his previous school. Both movies include a scene where he has become upset at school and so he goes to an empty warehouse and does a solo dance with many acrobatic movements.

Footloose also was perhaps the first movie that featured country-western dancing. The story includes a scene where several of the town’s young people drive to a city where there is a big place with country-western music and dancing.

Both movies include amusing scenes showing the small town’s young people clumsily and shyly learning to dance. Then during the prom at the movie’s end, all these young people dance well and confidently. Because of this surprising improvement, the movie ends excitingly and inspirationally for the audience.

The movie includes three sermons preached by the pastor. The first sermon is when Ren attends the church for the first time, right after he has moved into the small town. The second sermon is in the empty church on a Saturday evening, when the pastor practices for the next Sunday sermon he plans to give on the next morning. The third sermon is on the next, Sunday morning, when the pastor delivers a changed sermon (not the practiced sermon) in which he informs his congregation that he has adjusted his attitude toward the dance controversy.

The first two sermons in the 1984 movie are substantially different from the two corresponding sermons in the 2011 movie. In the 1984 movie, the two sermons are angry-God sermons, but in the 2011 movie the two sermons are kind-God sermons.

In the 1984 movie, the Sunday-morning sermon threatens the congregation with God's wrath and punishment:

He [God] is testing us. Every, every day, our Lord is testing us. If He wasn't testing us, how would you account for the sorry state of our society, for the crimes that plague the big cities of this country, when He could sweep this pestilence from the face of the earth with one mighty gesture of His hand?In contrast, the 2011 movie's Sunday-morning sermon calls on the congregation to turn away from modern, big-city life in order to appreciate and return to old-fashioned qualities of traditional, small-town society. Ren has just arrived in this small town and is sitting in the congregation, and so he himself is being challenged by the sermon to adjust himself to this small-town society.

If our Lord wasn't testing us, how would you account for the proliferation these days of this obscene rock and roll music, with its gospel of easy sexuality and relaxed morality? If our Lord wasn't testing us, why, He could take all these pornographic books and albums and turn them into one big fiery cinder like that!

But how would that make us stronger for Him? One of these days, my Lord is going to come to me and ask me for an explanation for the lives of each and every one of you. What am I going to tell him on that day? That I was busy? That I was tired? That I was bored?

No! I can never let up! I welcome his test. I welcome this challenge from my Lord, so that one day I can deliver all of you unto his hands. I don't want to have to do any explaining! I don't want to be missing from your lives!

We have computers in our pockets, phones in our cars, money on a plastic card. How many people here remember going inside a bank to get your money? Remember Old Mr. Rucker? Every time you made a deposit, he’d give you a piece of Bazooka chewing gum. I’ve never met an ATM that made me feel special like Mr. Rucker did. Is that progress?

Why take a family vacation when you can watch TV together on the couch? They claim that the television is a portal to the world, but don’t be fooled. That television is a portal of lies, morally degrading music videos, reality television?

What reality? I see nothing but the most base human cruelty and dysfunction. I see a celebration of unholy wealth that does nothing to reward hard work, but simply feeds off the sinner’s desire to be seen, to be noticed, to be used.And in the 1984 movie, the Saturday-evening practice sermon is heard by Ariel when she comes into the empty church in order to confront her pastor father:

If that’s a portal to the world, then I want no part of it.

These [pointing to the congregation] are the people we have to tune in to -- everyone in this church. This is our social network. And we don’t need Facebook to do it

There’s only one book [picking up his Bible] we need!

And I beheld and heard an angel flying through the midst of Heaven, saying with a loud voice: “Woe, woe, woe to the inhabiters of the Earth.”The pastor interrupts this practice sermon when he notices that his daughter Ariel is watching him, and then they have a conversation about their entire situation.

And I saw a star fall from Heaven unto the Earth, and the angel was given the key to the bottomless pit. And he opened the bottomless pit, and there arose a smoke out of the pit as smoke of a great furnace. And the sun and air were darkened by reason of the smoke of the pit.'

In the 2011 movie, the pastor’s Saturday-evening practice sermon is seen by Ren (instead of by Ariel), when he comes into the empty church. In a preceding scene, Ren had tried his best to convince the town council to permit dancing, but he had failed. The town council voted to maintain the ban. Now when Ren walks into the empty church, he sees the pastor practicing a sermon about how faith can overcome all obstacles. Faith is like a mustard seed that can grow into a tall tree. Faith can move mountains. Ironically, the pastor’s practice sermon inspires Ren to continue his efforts to remove the town’s prohibition against dancing.

The pastor's Saturday-evening practice sermon also expresses the pastor's own hopeful desire to overcome his own daughter's rebellion and to resume raising her to become a proper Christian adult.

The two sermons in the 2011 movie are more characteristic of modern Christianity in the USA, and they also support the movie’s story and theme more intelligently.

After the Saturday-evening practice sermon, the pastor gives the movie's third sermon before the entire congregation on the following Sunday morning. This sermon is similar in both movies. In the 2011 movie, the pastor says:

I’m standing before you today with a troubled heart. I’ve insisted on taking responsibility for your lives. But I’m really just like the first-time parent who makes mistakes, learns from them as he goes along. And, like that parent, I find myself at that moment when I have to decide:

Do I hold on?

Or do I trust you to yourselves?

Do I let go and hope that you’ve understood my lessons?

If we don’t start trusting our children, how will they ever become trustworthy?

I’m told that the senior class of Bomont High School has secured the use of a warehouse in nearby Bayson for a senior dance. Please join me to pray that our Lord will guide them in their endeavors.

The movie has a further moral lesson, which is that helping other people requires personal virtues – such as good judgment, effective communication, willingness to compromise, and accommodation of other people’s concerns.

After all, the pastor and other older people in the town banned music for a well-intentioned reason. They wanted to prevent other tragedies that might be consequences of future dances. They did not want any more pregnancies, any more drunken automobile accidents.

The eventual compromise on this issue was accomplished between the pastor and Ren. The pastor had lost his son, and Ren had lost his father, and so they instinctively reached out to each other, overcoming their initial hostilities toward each other.

Ironically, Ren turned out to be the most well-behaved and constructive young person in the small town, although he has come from a big city and has decided to challenge the dance prohibition. Ren wore a tie to his first day of school. He rejected a school-mate's offer of some marijuana. He rejected Ariel's seductive advances.

Ren followed proper procedures to change the dance policy. He collected signatures on a petition and he addressed the town council. He used the Bible as a source of arguments in favor of dancing. When the town council nevertheless maintains the dance ban, he decided to organize his dance legally in a neighboring town rather than violate his own town’s ban. Then, he asked the confounded pastor's permission to take his daughter to the dance, saying he himself would not go if the pastor still disapproved.

In every step of this dispute, Ren complied with the rules and mitigates his adult opponents’ concerns, and therefore he gradually was able to prevail. His dance took place, and everyone was happy at the end.

Likewise the pastor is proper, thoughtful and respectful in every step of the dispute. These virtues are apparent in both movies, but are much more apparent in the 2011 movie. The pastor listens to his wife, to his daughter and to Ren, and eventually he adjusts his opinion The pastor does not approve the dance, but he agrees not to oppose it. He then exerts his influence in a sermon to his to persuade his church congregation to adjust their own opinions likewise.

One of the soundtrack songs, “Holding Out for a Hero”, the lyrics of which were written by Pitchford, expresses female desire for males who are courageous -- who are invigorated by struggle, who are "fresh from the fight":

Where have all the good men goneIn this song, a young woman yearns for a male hero whom she can admire as a god. She does not compare this ideal man to the God of the Christian religion, but rather to a god of the Greek religion – Hercules, riding like a white knight on a fiery steed. The young woman feels she should hold out for such a hero, despite her impatient passion.

And where are all the gods?

Where's the street-wise Hercules

To fight the rising odds?

Isn't there a white knight upon a fiery steed?

Late at night I toss and turn and dream

Of what I need.

[Refrain]

I need a hero.

I'm holding out for a hero 'til the end of the night.

He's got to be strong,

And he's got to be fast,

And he's got to be fresh from the fight.

I need a hero.

I'm holding out for a hero 'til the morning light.

He's got to be sure,

And it's got to be soon,

And he's got to be larger than life.

Somewhere after midnight

In my wildest fantasy,

Somewhere just beyond my reach,

There's someone reaching back for me.

Racing on the thunder and rising with the heat,

It's going to take a superman to sweep me off my feet.

[Refrain]

Up where the mountains meet the heavens above,

Out where the lightning splits the sea,

I could swear that there's someone somewhere,

Watching me.

Through the wind and the chill and the rain,

And the storm and the flood,

I can feel his approach,

Like the fire in my blood.

One irony of the Footloose story is that the pastor's daughter has been sexually spoiled by a local boy who dislikes dancing, not by Ren, the city boy who has come to the small town and who will overturn the dancing prohibition and will organize the first dance. Furthermore, when the pastor's daughter approaches Ren seductively, he refrains from involving himself sexually with her.

At the end of the movie, just as the dance is beginning, this local boy comes to the dance and tries to disrupt it. However, Ren, with some help from Ariel, beats him up and chases him away.

This scene resonates with a scene earlier in the movie, when Ariel physically attacked this local boy, but he beat her up decisively. Ariel alone was not able to eliminate this local boy, this sexual mistake, from her life until she found her real male hero who actually deserved her admiration and love.

Ren deserves Ariel's admiration and love not only because he is courageous, but also because he is virtuous. Ren has won the admiration of her parents, of her school-mates, of her entire community.

The movie Footloose treats the Christian religion in an intelligent and interesting manner. A Christian family's eldest son has died in a car accident several years ago, and the pastor father and daughter still have not reconciled themselves to the finality of that death. The pastor father compensates by trying to over-control the town's youth, and the daughter acts out in risky misbehavior that includes sexual promiscuity. The mother is ineffective in dealing with her still troubled husband and daughter.

Several other young people died in that same car accident, and so the entire small town remains troubled. Every annual graduation of students from the local high school is associated emotionally with the idea that many of the new young adults will die suddenly. This premonition of death causes many of the young people to engage in risky misbehavior.

This troubled Christian family encounters a young man who has come to their religious small town from a large city and upbringing that has made him rather uninfluenced by Christianity. This young man too has suffered losses in his own family. His father abandoned him when he was a small child, and (in the 2011 movie) his mother has died of leukemia. This boy still suffers emotionally from these family losses, although he is able to relieve his stress temporarily by dancing in private.

The boy decides to give his own, mortal life meaning by exerting himself to make a positive change in the small town, even though he still is a semi-stranger there. He campaigns to overturn the town's dance prohibition, but he does so in a manner that is cooperative and respectful.

Eventually the boy positively influences the Christian family. The pastor father learns to trust the town's youth, and the daughter stops her rebellious, promiscuous misbehavior.

The audience can foresee that he will marry into and join that Christian family and will to some extent replace the son who died in the car accident.

Essentially, the movie addresses the fear and eventual certainty of death to which young people must reconcile themselves as they leave their families, schools and communities and go out as new, young adults into the outside world. Mortal life becomes meaningful for a person when he leads a virtuous, courageous, proper social life, making positive contributions and changes for other people around you. Such a life, despite eventual death, becomes joyous and can be celebrated my means of dance and other arts.

No comments:

Post a Comment